- Are you homeschooling a kids with special needs like Dyslexia or Autism?

- Does your kid cry and have a meltdown for every writing assignment?

- Do you avoid doing writing in your homeschool because it is just so hard for your child?

- Have you gone from one grammar and writing curriculum to the next searching for one that actually will work for your child with special needs?

- Do you ever wonder why your student is bursting with information verbally, yet can hardly write a word without anxiety?

This article may help to answer some of your questions, provide some guidance about how to help, and share with you my tool to actually help kids launch as successful writers without all the stress.

Here’s the WHY behind the difficulty of LEARNING to write.

Writing is the most difficult academic skill for any learner. Sometimes it feels impossible for kids with language-based learning difficulties, like autism and dyslexia. The task of completing a written expression task involves all of the parts of the brain involved with learning – literally.

Typically, writing is taught after a child learns to speak, read, and spell. Handwriting needs to be at a level that is somewhat legible or the student needs to have some skills with technology. Written expression is a complex language encoding skill involving multiple auditory processing skills. Writing also involves visual processing, working memory, executive functions that control organization and decision-making, the parietal lobe that controls movement, and the limbic system that controls emotions.

A writer much think of a topic, narrow it to a key idea, research as needed, organize the information, then get the information into print. The actual process of getting words on paper involves thinking in complete sentences, correctly spelling words, and using mechanics properly. In a paragraph, add a level of organization by sequencing ideas in a logical order that communicates in print to a reader. Finally, a writer must know when a work is worthy of revision and have both humility and confidence to proofread, edit, and revise their work. No wonder our struggling learners have trouble with writing!

Often, we expect a student to automatically write as well as they speak or read, which is nearly always an unreasonable expectation. When a toddler is learning to speak, we get so excited when they speak their first sounds, words, phrases, and finally a complete sentence! We expect a child to learn the alphabet, phonics, and decoding skills before reading fluently. It makes sense that a kid will learn multiplication facts prior to learning the long multiplication or division process.

Systematic progression makes sense in every skill area. We give explicit teaching in each of these skills, yet we either think writing should be an easy extension of speaking or an enigma in how to make it happen. Keep reading. I will help you see that even for kids with special needs, writing is somewhere between super easy and impossible. I’ll also show you how to take your tween or teen, wherever they are in the process of writing paragraphs, to the next level.

Read this if you’re asking, “How do I get my kid to write a paragraph?”

Scaffolding helps unique learners maneuver the process successfully.

Teaching writing can be heart-wrenching, especially for homeschool moms of a kid with special needs. The two most common requests about writing I’ve heard from homeschool moms have been how to teach writing and how to evaluate a child’s written work. This article will cover how to teach paragraph writing to kids with special needs and transform your homeschool, tutoring sessions, or special ed classroom. I’m going to show you how to set up writing for success, and how to tweak what you do to get as much written language out of your kiddo as possible. You and your child may even look forward to writing time!

First, no matter what subject I am teaching, I like to use a scaffolded progression similar to the 3 Period Montessori Lesson: Naming, Recognition, and Recall. Only for writing, I use: I’ll show you. We’ll do it together. You try. This lesson progression and the use of a graphic organizer is intentional scaffolding that can be effective for any learner.

What is scaffolding?

Scaffolding is a teaching term that means structural support, just like construction workers use a scaffold to build a house. The scaffold structure is there for the support of their work on the actual project, not to do the work for them. Sometimes all the worker needs is a ladder; other times a series of platforms is needed.

Second, the terms modifications and accommodations are thrown around a lot by schools for kids with an IEP or a 504 Plan. As homeschoolers we need to know how to make adjustments to meet the needs of our kids also. There is a difference between modifications and accommodations.

What are modifications?

As homeschoolers, we think less about modifying a curriculum because many times moms expect the curriculum to already be tailored to their own children, even though we like to talk about how each kid is a unique learner. The writers and publishers of curriculum don’t know your children. It can be very freeing to know that YOU are the teacher, not the curriculum you purchased. The program you pick is just a tool to help you accomplish the task of instructing. If the tool doesn’t work, then you may need to modify or change it somehow. That doesn’t mean you need to scrap it and find a different one! This is one of the reasons I prefer to teach using goals rather than relying on one specific curriculum. I find the core curriculum I like for my kids. Then I add supplements or eliminate things that just don’t fit them.

What are accommodations?

Accommodations are the little adjustments we make for each child based on their learning preferences or their need to succeed within the chosen curriculum. Schools may use the word “differentiation.” An older term is individualization. One of the beauties of homeschooling is that we can make accommodations for all of our kids without a formal IEP process or even qualifying for a service. We just do it.

Accommodations may be as simple as asking for only 10 math problems instead of 30 or making the print larger for reading. In writing, the most basic accommodation is to have a kid dictate their ideas and then trace, copy, or type what they dictated. Start with one sentence at a time. Work your way up to 5 separate sentences. Then you will know that your kid will be able to handle writing a paragraph.

Dictating allows our kids with special needs to use the skills they already have to communicate while learning to translate those words into a different language form – printed text. The model for mechanics and spelling gives students opportunities to find a voice and share their knowledge through correct practice rather than reaching frustration point when left to remember all the nuances of written language. I have found that kids want to be independent when they are given the accommodations and scaffolding needed to be successful. Remember, I am mainly talking about kids with language-based learning issues; however, the same principles work well for younger, neurotypical kids.

Here’s my process of teaching paragraph writing

I have found a system for teaching how to write a paragraph that actually helps kids want to write. My system involves explicit instructionof a simple formula for paragraph development. For nearly every subject area, I tend to follow a sequence similar to the 3-period Montessori lesson.

Here are the three parts of teaching writing.

- Explain and Model. “I’ll show you how.”

- Supported Practice. “Let’s do it together.”

- Try It. “You can do it with the helps you need. AND you are safe.”

Explain and Model. “I’ll show you how.”

During the Explain and Model phase, I introduce the parts of a formatted paragraph as a whole. Then I break down the lessons to teach each piece separately.

Using a Montessori-based lesson sequence to teach paragraph writing, I start by explaining and modeling the structure of a paragraph. I have simplified the structure to the cue “T123C.” The T-3-C rhymes, making it easy to remember. For my students who tend to remember visual cues, I also share the hamburger analogy while relating it back to the T123C cue. Sometimes I have the student draw a hamburger and insert the T for the top bun, 123 for ingredients they select, and C for the bottom bun. I always prefer for my students to create their own personalized drawings rather than providing premade handouts that have no meaning for them. The more students can DO something that builds on their own prior knowledge, the more they will remember the concepts.

- Topic Sentence. A topic sentence, “T,” must have a topic and a key idea. Any topic can be broken into a key idea, which narrows the topic to something manageable to write about. We start with the simplest way to write a topic sentence: Use the topic and key idea phrase in a sentence.

- Types of Topic Sentences. Once the student becomes familiar with stating a topic sentence, I introduce the 3 types of topic sentences: general, cuing, and specific. Kids usually grasp specific easiest because all they have to do is list the detail items in the order they want to write about them. I have them practice using a general for the topic sentence and a specific for the closing sentence and then switch them around. I provide a handout of cuing words when a student is ready to add cuing topic sentences to their repertoire. Then we practice mixing and matching topic sentence types.

- Detail Sentences. The details are the “123” part of the paragraph. I repeat many times that 3 is a good number of details; however, the minimum is 2 detail sentences and the maximum is 10. Mostly the 10 is to help kids know they are encouraged to write more; I honestly never have students who plan ten details because struggling writers just don’t use many words in writing. They just don’t use many words! Expressive language is also the underlying reason that students with dyslexia and autism often want to just make lists rather than write in complete sentences. The planner on my paragraph template helps them make their list first. Then I can guide a student with more severe language issues to put their ideas into sentences. I provide a handout of transition words and phrases when a student is able to logically plan the sequence of the details in a paragraph and add follow-up sentences to expand the information in each detail. Usually this transition words handout is printed on the backside of the cueing words handout so the student has a handy reference sheet.

- Closing Sentence. When writing the closing sentence, “C,” we simply paraphrase the topic sentence. Kids think they said it once, so why say it again. I like to tell my students that the closing sentence tells the reader, “I’m done.” I explain to my kids that if they don’t close the paragraph, readers expect them to keep going. It’s funny because once I explain the purpose of a closing sentence, students will at least rewrite the topic sentence just so they can be done! LOL

COPS Proofreading. Once the paragraph is written, I model using a proofreading acronym, COPS, which is simpler than many proofing checklists. We are pretending to be writing police to check if rules are followed. Together, we look at:

- C=Capitals – Beginning of each sentence. The word “I.” Names.

- O=Organized – Are the sentences complete? Are they in a logical order?

- P=Punctuation – Ending periods. Commas in lists. Commas for compound sentences.

- S=Spelling. One of the quickest ways to squash a child’s fascination with writing is to over-emphasize spelling. I will talk about spelling more in the next section. Unfortunately, the fear of spelling words correctly leaves our kids with special needs immobile and completely resistant to writing. Spelling is actually the least important feature of writing because it can be corrected by someone else. I like to tell a resistant student, “No one can know what is inside their head. I can’t think your thoughts for you. However, I can fix your spelling.” Since spell checking is an external task, it is less important than the O part of COPS.

Supported Practice. “Let’s do it together.”

During the Supported Practice phase, I lead the student or group in writing a shared paragraph using the formatted graphic organizer. Depending on the situation, I may write on chart paper, a whiteboard, or regular paper – but I prefer to use a graphic organizer throughout the entire instructional process. I typically present 2 or 3 topics and allow the students to suggest another one. The student decides the topic we will write about.

If needed, we look up information using the topic and key idea as the search keyword. Even by briefly looking up information, students get the message that it is ok to research and seek out additional information rather than relying solely on memory. Even teens with very low reading skills love the independence of researching by using the microphone on a Google search bar! If we are creating a student-made book, we may also select images to integrate into our project.

Using questioning (a modified Socratic method), I draw out the planner items and lead the students in translating the notes to complete sentences following the T123C format. I write the sentences, but since the students have the form or paper, I often see them copying without even asking. Of course, that warrants enthusiastic praising and celebration!

Positive systems for proactive practice set up teachers for effective modeling and students for accelerated learning!

I want my kids to use tools to assist with spelling in case I am not around to help. I show all my writers how to use the spell check features and the voice-to-text feature in Google Docs or MS Word. Grammarly can be another great tool; however, for some kids Grammarly may point out too many of the quirks in their expressive language which becomes discouraging, so I typically suggest Grammarly to more advanced writers.

A guaranteed writing “squasher” is to underline misspelled words for a kid to copy 3 to 5 times. I prefer to incorporate spelling correction into the natural revision process to reduce frustration and shame. If a child makes more than 5 spelling errors when independently writing a paragraph, you may want to consider the accommodation where the student dictates and you scribe. Then have the student do something with their dictated words. They could trace or copy it so that spelling is modeled into the writing activity. The model can be used to type into Google Docs or MS Word.

Remember that accommodations allow a student with special needs to accomplish the same writing assignment without carrying the entire burden of the writing process. We always want to give as much support as is needed, while simultaneously giving the minimum support for the learner to be as successful and independent.

Try It. “You can do it with the helps you need. AND you are safe.”

and accommodations, you can have a happy writer!

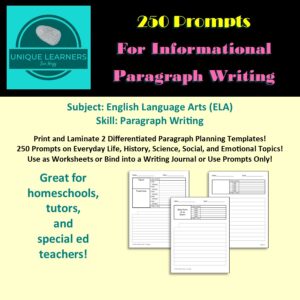

By the time we reach the Try It! phase, the student is very familiar with the formatted graphic organizer. I print out my set of 250 writing topic prompts for informational paragraph writing. Later, we will move to writing for different purposes, but for now I want the student to practice being confident and over-learning the process of generating a paragraph with ease.

The graphic organizer format stays the same. The process stays the same. The topic prompts all support narrowing to a key idea. I like kids to have choices and a sense of control, so for each independent assignment I provide 2 to 3 of the writing prompts. Some of my students prefer to have a laminated blank graphic organizer. The student does their planning while I am available to coach as needed. Once the planning is done, the student will either write the informational paragraph, type it in Google Docs or MS Word, or use the voice-to-text feature to dictate.

I repeatedly teach the formula, types of topic sentences, how to translate ideas into sentences, how to add transition phrases, and how to proofread. I keep writing as simple as possible. I have found that the “six traits of writing system” is typically too complicated for my students with dyslexia or autism. The formatted graphic organizer and the 250 writing prompts help me to provide the scaffolding my students need. I also have a second graphic organizer for students who are ready to add transition phrases in the detail sentences. Any part of the writing prompt pages may be used for the student to dictate and then either copy, type, or use the voice-to-text tool in Google Docs or MS Word.

If you want to use my set of 250 paragraph writing prompts for up to 5 details, you can find them in my TPT store! My advice is to allow a child to over-learn this skill prior to raising the expectation, just as they would learn phonics and decoding skills prior to the expectation of fluent reading or learning multiplication facts prior to learning the long division process. Systematic progression makes the most sense to my students. I even use this system with my high schoolers who are preparing to write essays. Eventually, we move to writing a thesis and college-level research papers with sources. That is why I spend much more time helping my students formulate great paragraphs rather than creative story writing.