Researchers have discovered that, to some extent, humans have an innate sense of numbers. In early childhood, we have kids practice rote counting up to 20, practice counting a few objects, and help them trace numerals (the symbols for numbers). Most neurotypical kids move through these math milestones with minimal stress. Some kids will have a little hurdle with number names between 10 and 20. Although our brains can do some number tasks naturally, arithmetic and higher math skills must be taught. That is often when it becomes apparent that a child has math struggles with some fundamental math skills.

So we often forge forward and introduce addition, hoping that demonstrating how addition relates to counting will help the child make sense of numbers. Sometimes the result is years of addition practice that still doesn’t help a child with a math disability to progress.

However, there is hope. The first step is to go back to the innate sense of numbers to be sure those are intact. Then explicit instruction in what the four operations do to numbers can often get kids who have been stuck over the hurdle of concepts and experience forward movement in math.

So what are those built-in brain skills that wire us to learn math? The three math skills are subitizing, conservation of numbers, and 1-to-1 correspondence. Keep reading to find out what these foundational math skills lead to in learning elementary math.

Math Skills #1: Subitizing

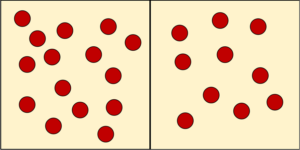

Subitizing is a sense of what set of numbers has more or less without actually counting. Neurotypical children can often recognize the values of 1, 2, and 3 even as infants! Some toddlers can recognize groups that have more or less in random configurations up to 30 objects or dots! Many kids with developmental issues have great difficulty with more and less. Once they can recognize more, having the flexibility to recognize less is also important. Subitizing and knowing more/less are the underlying concepts that build toward the idea of balance for relational terms, like “equals,” “greater than,” and “less than.”

Here’s how you can check if your student can subitize, even if the learner is a teenager with more severe learning issues and math struggles. Take some index cards and place dot stickers randomly on each card. Make cards that have 1 up to 20 stickers. Place two cards side by side and ask your student to point to the one with more without counting. Allow enough time to respond, but if the learner starts to point to the dots to count, remind them just to show you which one has more. Then change to another set of cards. They should be able to correctly identify “more” 4 out of 5 times or 8 out of 10 times. If not, then you know to back up to work on subitizing for instruction.

To teach subitizing, use the same cards and prompt as before. Whenever the student responds correctly, praise the correct answer. When the answer is incorrect, just point to the correct card and say, “This one is more.” Do not count the dots. If the student still doesn’t understand after working on more for a few days, put two cards side by side and draw lines to match dots on each card. The one that has leftovers has more. Keep practicing until your student reaches 80%. Once your student is consistent with identifying more, turn the answer around to identify less and fewer. Sometimes the language is confusing to students with math struggles. Limit the vocabulary exchange until one prompt is consistent.

Math Skills #2: Conservation of Numbers

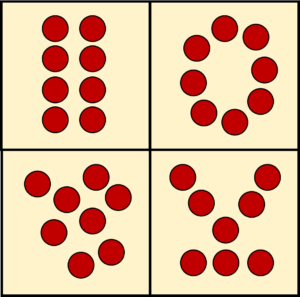

Conservation of numbers is a sense that objects can be rearranged and, if you observe that nothing was added to the pile or removed from the pile, the quantity remains the same. Neurotypical children often sense that the quantity is the same just by observing how everyday household objects are moved around. One example is counting out silverware for setting the table, holding the quantity, then distributing the utensils at each place. The quantity hasn’t changed, but the position has changed several times. The foundational math skill of conservation of numbers leads to the ideas of the commutative property, associative property, and eventually the distributive property.

To check if your student has the sense of conservation of numbers, take a pile of counting chips. Start with about 7 to 10 items. Put them in a pile. In front of the child, spread them out. You count the chips and state how many are there. Then rearrange the chips in front of the child to a different arrangement without adding or removing any chips. Sometimes put them in rows; sometimes in circles, sometimes in a random arrangement. Ask the child, “ How many are there now?” A child who has the foundational skills of conservation of numbers will automatically say the amount you set out. If your child is compelled to count them every time you rearrange the chips, then you know to back up and directly instruct conservation of numbers.

To teach conservation of numbers, do the same task that you used to check on the skill. Make it funny like you are working on a magic trick. Start with only 3 items. You count them. Rearrange the chips. Ask, “Did I put any more in the group?” Your child should answer, “No.” If your child says yes, then do it again, and have them watch closely. Ask again. Continue to rearrange chips until the child is able to say that there are still only 3 items. In another lesson, use a few more chips. Follow the same procedure. Continue to practice conservation of numbers until your student with math struggles can say confidently the given number without counting, even when the chips are rearranged.

Math Skills #3: One-to-One Correspondence

The third foundational skill that most kids just pick up, but some kids need to be taught is one-to-one correspondence. This skill is that each number when we are rote counting represents one object. This skill sets up the underlying concepts that lead to being able to do any of the operations. Young children often can learn to do 1:1 correspondence up to 10 items; however, many of my students with math disabilities, even the teens, have great difficulty going beyond 10 and sustaining accurate 1:1 correspondence. Sometimes this is a language issue because 2 objects are often counted with number words that have two syllables. Like two counting chips or pennies may be counted for “thir-teen” or “four-teen.” This is important to correct because these same learners often have difficulty with addition because they don’t understand how to count on and miscount based on the number words. Some kids just touch items swiftly without a synchronized rhythm between what they touch and what they say.

To check if your student has accurate 1:1 correspondence, set out a pile of counting chips that has more than 10 items in the pile. Ask the child to count the chips. Do not assist; just watch. See what happens when they count beyond 10. If the student touches more than one chip for number words that have 2 syllables, then you know this is likely a language issue. If the student just randomly touches chips and the pace doesn’t match the count, you know this is a foundational concept that is misunderstood and must be taught.

To address the language issue, it sometimes helps to make index cards with the numbers on them. Hand the student a bunch of chips. Have them place one chip on each card. Then touch and count the chips on the cards. The final count should match the written number. Continue practicing on numbers, then off numbers until the student can count the correct number consistently over the course of several days.

To instruct the concept, it helps to use a modeling technique. Place a pile of counting chips on the table. Start with numbers less than 10. First, model how to arrange the chips in a pattern of rows of 5, eventually working up to groups of 10 using a ten-frame manipulative. Once the items are arranged in rows, individually count the items by touching each one slowly as you count. Announce the correct answer. Mix up the chips and have the student do what you did by making rows and counting the chips by touching each one. The student’s answer should match yours. Continue practicing counting quantities between 10 and 100 until the student can count accurately 9 out of 10 times. Playing games to move along a path also helps with 1:1 correspondence. Be patient, though, because what may seem to be cheating from miscounting spaces may actually be a math problem with 1:1 correspondence. The more you practice in the teens and beyond, the easier the skill becomes for kids with math struggles.

What Next?

Once your child has mastered subitizing, conservation of numbers, and one-to-one correspondence, I typically teach touchpoint numbers. This allows us to build on these foundational math skills to accurately do addition and subtraction without memorizing facts. I prefer to work toward skip counting and multiplication facts. If I know that a student has had difficulty with foundational concepts, I can anticipate that other concepts, such as place value and the purpose of the four operations will need to be explicitly explained and practiced to mastery. Math skills are best learned and mastered when integrated frequently with daily living skills, like telling time, money, and measurement. Students with math struggles also require explicit instruction with a spiraling program that continually reviews skills that have been introduced, practiced, and mastered in order to maintain and see the connections with new math skills.

One of the problems with this approach is that finding a math program tailored to a unique learner with math struggles is nearly impossible. So homeschool parents and special needs tutors need to be persistent in finding supplemental materials that can enhance what has already been worked on. If you need assistance in programming for your unique learner, feel free to email me at uniquelearnersllc@gmail.com for some advice!

Grab your FREE e-book guide to revamp your homeschool for success!

Are you new to homeschooling, or just wanting a fresh start? Download our FREE “How to Homeschool in 6 Easy Steps” guide and get valuable insights from Sue’s 30+ years of experience as a special educator and homeschool mom of 4!

Want to know about new products and blogs?

Join our email newsletter to be the first to know about a new homeschool and special needs blog, and new products from our shop! Sign up for only the newsletter, or grab your FREE “How to Homeschool in 6 Easy Steps” guide and you will also be added to the newsletter!

Also, join our Facebook group!

Join our new “Homeschool Help for Special Needs” Facebook group! It is a place for homeschool moms to ask questions about homeschooling a child with special learning needs, share teaching and curriculum ideas that have worked (and those that bombed), and be real about the unique challenges of homeschooling with special needs. If you want to join us, be sure to answer the member questions to help us keep this private group secure. Join us now!